Welcome to Turning Corners: inspiring stories about the people and organizations working to make life better in the Four Corners states of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado. It’s a new podcast produced in Santa Fe, NM, by me, Wade Roush. Listen to the trailer for more about who I am, why I started the show, and what it’s going to be about.

For this first full episode of the show, I went inside Santa Fe’s Georgia O’Keeffe Museum to talk with artists and curators about a daring new exhibit called Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country. The exhibit is an act of community storytelling, meant to both illuminate and soften some of the old boundaries and tensions between indigenous artists and the Anglo art establishment O’Keeffe represented.

The exhibit features the work of a dozen artists from the six Tewa-speaking pueblos of northern New Mexico. All express in different ways their love of the vibrant land their people have inhabited for hundreds or thousands of years—and all grapple with the way O’Keeffe, still America’s most famous female artist, repeatedly framed the landscape around Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu as an empty, silent realm that she alone could properly interpret.

“It’s my private mountain,” O’Keeffe once said of Tsi-p’in or Cerro Pedernal, the striking flat-topped mountain visible from her home. “It belongs to me. God told me that if I painted it enough, I could have it.”

In point of fact, the mountain is on U.S. Forest Service land, and is the site of Tsi-p’in-owinge, a ruin that was the ancestral home of the people of Nambe, Ohkay Owingeh, Pojoaque, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, and Tesuque pueblos. So O’Keeffe’s quote—even if it was meant in a poetic or tongue-in-cheek way—rings in modern indigenous ears as a provocation.

And indeed, for Jason Garcia, the Santa Clara Pueblo artist who co-curated the Tewa Nangeh exhibit, it served as an organizing theme. He worked with curator Bess Murphy at the O’Keeffe Museum, and with the contributing artists, to gently but irrevocably overturn the idea that any one artist can speak for an entire region.

To find out how that happened—and how Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country is stirring up some long-overdue conversations—listen to the podcast here, or find it in your favorite podcast app. The full transcript is below.

FEATURED VOICES

Jason Garcia, who also goes by Okuu Pin (Turtle Mountain), is an artist from Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico who specializes in clay tiles and printmaking. He co-curated of the Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country exhibit (2025-2026) at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Garcia’s work documents the ever-changing cultural landscape of his home, including cultural ceremonies, traditions, and stories, and also draws on 21st-century popular culture, comic books, and technology. Garcia’s juxtaposition of traditional and contemporary materials and techniques connects him to his Ancestral past, landscape, and cultural knowledge. He studied fine arts at the University of New Mexico (Bachelor’s, 1998) and the University of Wisconsin (MFA, 2016).

Bess Murphy, PhD, is the Luce Curator of Art and Social Practice at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She joined the O’Keeffe Museum in 2022, and Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country, which she co-organized with Jason Garcia, is her first curated show at the museum. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Bard College and a PhD from the University of Southern California, and from 2015 to 2022 she was the creative director and curator of the Ralph T. Coe Center for the Arts in Santa Fe.

Michael Namingha is a photographer and silkscreen artist who hails from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo in New Mexico and the Hopi tribe in Arizona. His work, which often features surrealistically altered images of the natural landscape, has been featured in solo and group exhibitions at galleries and museums around the world, from New Mexico to Arizona, California, Indiana, Maine, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Texas, and Virginia, as well as Canada, Germany, and Japan. He splits his time between Santa Fe and Brooklyn, where his studio is located. He studied strategic design and management at the Parsons School of Design.

Wade Roush, PhD, is the creator and host of Turning Corners. He’s an MIT- and Harvard-trained freelance science and technology journalist, editor, and audio producer who has written for publications such as Science, MIT Technology Review, Xconomy, and Scientific American. From 2017 to 2025 he produced the tech-and-culture podcast Soonish. He’s the co-founder of the Hub & Spoke audio collective, the author of Extraterrestrials from the MIT Press, and the editor or co-editor of three volumes of hard science fiction: Twelve Tomorrows (2018), Tasting Light (2022), and Starstuff (2025).

TRANSCRIPT

<Hub & Spoke sonic ID>

<Cue theme music>

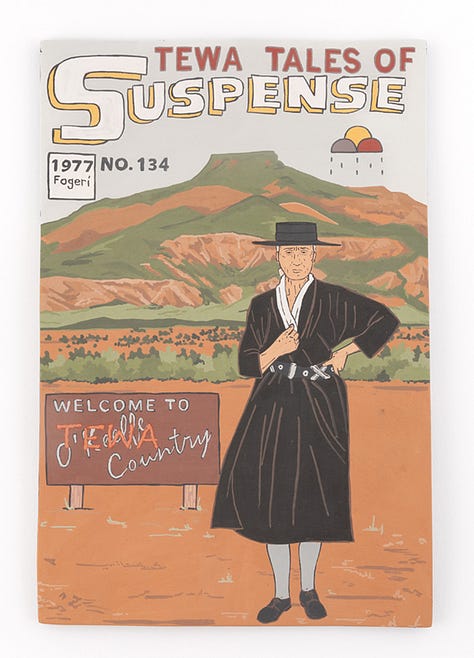

Jason Garcia: And the image is a portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe standing within the Tewa landscape with the mountain Tsi-Pin, also known as Cerro Pedernal. And there’s a sign that’s a billboard that says welcome to O’Keeffe country. And then over the top of O’Keeffe it says Tewa Country.

Wade Roush: Today on Turning Corners, a visit to Tewa Country. That’s the name of a new exhibit at Santa Fe’s Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, where Jason Garcia from Santa Clara Pueblo is one of the show’s stars and curators. He says the exhibit’s designed to change the way we think about New Mexico’s most famous artist and the people who actually live on the land she painted.

< theme music>

Georgia O’Keeffe archival tape: When I got to New Mexico, that was mine. As soon as I saw it, that was my country. I had never seen anything like it before, but it fitted to me. Exactly. That’s something that’s in the air. It’s just different. The sky is different. The stars are different. The wind is different. I shouldn’t say too much about this, because other people may get interested and I don’t want them interested.

Wade Roush: Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings of giant flowers had already made her a popular figure on the New York art scene by 1929, when she spent her first summer in northern New Mexico.

She came here because she was looking for an escape from the social whirl orchestrated by her famous husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

And later she told interviewers over and over that she realized right away that New Mexico was special. It was where she would find everything she needed to reinvent herself as a painter. Specifically, a painter of landscapes.

Georgia O’Keeffe: The cliffs over there. You look at it and it’s almost painted for you. You think. Until you try. I tried to paint what I saw. I thought someone could tell me how to but I found nobody could. They could tell you how they painted their landscape. But they couldn’t tell me to paint mine.

Wade Roush: That very first summer in New Mexico, O’Keeffe bought a Model A Ford. One day she was taking driving lessons near the village of Abiquiu when she got her first glimpse of a rugged, picturesque canyon called Ghost Ranch. She recalled thinking that day, “This is my world.”

Years later she bought an adobe house at the mouth of the canyon, and in 1949, after Stieglitz had died, she started living there full-time.

Now, I’ve been to the Ghost Ranch house, and here’s the thing. From the central courtyard there’s a view of a mountain with a striking flat-topped silhouette.

The Spanish called this mountain Cerro Pedernal and the people of the local Tewa-speaking pueblos call it Tsi-Pin, which means Flint Mountain or Flaking Stone Mountain.

O’Keeffe started painting the mountain, from different vantage points and in different light. In fact, Pedernal became such a potent symbol for her that she ended up painting it 29 times.

And many years later, in 1977, she was speaking to a reporter from Newsday when she said something interesting about Pedernal. She said, quote, “It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.”

You can understand why she felt this way.

It’s very common for modern artists to fall in love with a subject, to paint them endlessly, and to end up feeling a kind of poetic but authentic ownership of this subject they know so well in every season, at every time of day.

Just ask Claude Monet or Paul Cezanne what it’s like to fall in love with a mountain.

O’Keeffe’s connection to Pedernal was so strong that she chose to have her ashes scattered over it when she died in 1986.

To her, she was its spiritual owner.

But of course, she wasn’t.

To get legalistic about it—the mountain is on U.S. Forest Service land.

More importantly, It’s the site of a ruin called Tsi-p’in-owinge that’s one of the ancestral homes of the people of the six pueblos of northern New Mexico that share the Tewa language—namely Nambe, Ohkay Owingeh, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, and Tesuque.

The point is, indigenous people have been calling the lands around Tsi-P’in home and representing the mountain in their own traditions for a very long time.

But the fact is that O’Keeffe’s fame as a painter grew to eclipse that of just about every other artist in New Mexico. In that context, a phrase like “My private mountain” becomes the grist for some understandable tension and resentment.

And that’s why I was standing recently in the middle of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum with artist Jason Garcia from Santa Clara Pueblo, looking at a piece of clay tile that he painted in the style of an old comic book cover.

Jason Garcia: So we talk about O’Keeffe country and this terminology, this myth, mythological term, uh, for this area. And uh, one of the pieces that I do have in the work is, uh, you know, greets the visitor as they come into, uh, this gallery space, which is a, uh, entitled tales of suspense number 134. And the piece is called Welcome to Tewa country. And so the tile is made from hand processed clay hand gathered clay that’s been gathered near Santa Clara Pueblo. And then it’s painted with different mineral pigments that have been gathered in different areas of northern New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and some Utah as well. And then it’s traditionally fired outdoors using traditional Pueblo pottery techniques. And the image is a portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe standing within the landscape with the mountain Tsi-Pin, also known as Cerro Pedernal. There’s a sign that’s a billboard that says welcome to O’Keeffe country. And then over the top of O’Keeffe, uh, says Tewa Country. So, you know, this refers to, uh, Georgia O’Keeffe’s, um, quote that appeared in Newsday, October 30th, 1977. And she said, “It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me.” The mountain is the starting point for the exhibition and the idea of the exhibition as well.

Wade Roush: So what is the idea of the exhibition?

Well, of course it tells the story of the art and the artists Jason Garcia recruited for the show. I’d say a lot of it is about this landscape they all love and the question of who gets to represent it through art.

And at the same time I think it’s fair to say that Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, as an institution, is saying something of its own through this exhibit. They’re using it to very publicly rethink their role in the larger community. And they’re beginning to present O’Keeffe’s work as part of a much longer story about the Northern New Mexico region that starts way before O’Keeffe ever got here.

Bess Murphy: I think for a museum like the O’Keeffe to be situated in Santa Fe, in northern New Mexico, it’s our duty to think about how the history goes beyond just this one individual figure.

Wade Roush: That’s Bess Murphy. She’s the Luce Curator for Art and Social Practice at the O’Keeffe Museum, and she worked alongside Jason Garcia to put together the exhibit. You’ll a lot more from her later.

Bess Murphy: And, um, for me, it was definitely like, how can we, how can we give away some of that, like authority and that room, that space, where she’s been so mythologized and open that up so that it’s like the O’Keeffe Museum takes a step back, right?

<sonic interlude>

I first saw Bess Murphy and Jason Garcia talking about the Tewa Country exhibit at a panel discussion last October. And as soon as I understood what they were trying to do, I knew that I wanted to use the first episode of Turning Corners to talk about it.

If you listened to the trailer for the podcast, you know I moved to Santa Fe a few years ago.

Now, in a lot of ways my personal story puts me in the same category as every other seeker who’s moved to northern New Mexico in the last 180 years, including Georgia O’Keeffe herself.

There’s a very long tradition of people, showing up here from Boston or New York or San Francisco or Austin, in search of artistic inspiration or spiritual fulfillment or maybe just because they feel something different in the air and the sky and the stars and the wind.

You can definitely feel this testing and stretching of perception in O’Keeffe’s work.

I’ve always loved her paintings of mountains and dead trees and bones.

Seeing them over the years gave me a kind of premonition of how magical this part of New Mexico must be.

But I still figured she must be embellishing or imagining or even hallucinating a lot of it.

When I actually moved here, I was astonished to see that nope, she was being pretty literal.

She saw this area not just for how it affected her personally, but for how it really was.

But she only saw part of it. Not the whole of it.

And the more time I’ve spent here, the more I’ve come to understand how many other people have their own ways of seeing and representing this land, some of them going back hundreds or thousands of years.

And that brings us back to the O’Keeffe Museum.

It’s the custodian of O’Keeffe’s estate, including her historic houses in Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu.

And its public collections are housed in a sun-filled, Pueblo Revival-style building that opened in downtown Santa Fe in 1997.

Exhibitions there over the years have celebrated everything about O’Keeffe, from her photography to her relationship with the land to her iconic black wardrobe.

And you better believe the larger community around Santa Fe gets on board with that celebration, which helps to fuel the regional tourism-industrial complex.

When I wandered into the local Trader Joe’s last week it was both a surprise, and kinda not, to see a huge wall mural of O’Keeffe at her easel, painting a flower.

Right below that, cleverly positioned above the actual flower section, there’s a line from O’Keeffe. It says, quote, “If you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world, for the moment.” Unquote.

Now, millions of TV viewers got a close look at one of O’Keeffe’s flowers recently when the show Pluribus sent its main character Carol inside the O’Keeffe Museum to steal a famous painting called Bella Donna, 1939.

But long before Pluribus was even a twinkle in Vince Gilligan’s eye, back in the pivotal year of 2020, when it felt like George Floyd’s murder and COVID-19 were turning everything in the country upside down, the real O’Keeffe Museum organized an online panel discussion called “This Is Not O’Keeffe Country.” And I think this is where the story of the Tewa Country exhibit really starts.

The chair of the panel was Dr. Alicia Inez Guzman. She’s a journalist from New Mexico who covers the nuclear weapons complex and many other subjects vital to this part of the state. And she kicked off by panel by framing some more of the history that O’Keeffe stepped into in 1929.

Guzman: When she arrives, of course, like many others who are coming from elsewhere, she falls in love with the landscape and the light, and she starts painting. And she moves to New Mexico for summers at first, and then eventually permanently, right around 1940. And so one quote that I think is especially important…for giving some context is, is she’s painting out in the Navajo Nation and which was one of her favorite places to paint. And she camps out there and she says “it’s such a beautiful, untouched, lonely feeling place. Part of what I call the faraway.” And in fact, O’Keeffe did a really great job of depicting this feeling of isolation and faraway-ness. And in fact, one of her paintings is called The Faraway Nearby. And I think this is what helps contribute to this idea that New Mexico is on the periphery, and that we start to see it through this lens in which it is isolated, and it is beyond the kind of, um, cosmopolitan frame that she was coming from. And so she reframes New Mexico yet again through this lens of isolation. And this is incredibly we have we have inherited this legacy of O’Keeffe. And so I think it’s really important to push back and to give context, because New Mexico is amidst change. When she arrives, the national laboratory is being built, there’s a new technology getting introduced into the landscape or the infrastructure is changing. Roads are getting built to allow materials to move to the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Um, we see the damming of the Chama River into the Abiquiu Dam. So the landscape is actually changing. Not only that, we have our native relatives who’ve been here for millennia. We have our, um, Hispanic and Chicano populations who’ve been here for the last 400 years, and it’s been an incredibly dynamic, vital, changing space. This is the New Mexico that O’Keeffe enters as a guest.

Wade Roush: The other panelists that night represented other parts of New Mexico’s indigenous and Chicano communities. They talked about how when O’Keeffe showed up here, alongside her contemporary Robert Oppenheimer, it was a huge boost for New Mexico on the national scene. But one of the results was to sideline the people who were already here. One of the speakers was Corinne Sanchez. She’s the head of an advocacy group called Tewa Women United that’s focused on environmental, gender, and reproductive justice.

Corinne Sanchez: You mentioned Los Alamos National Laboratory, and Oppenheimer fell in love with the scenery here in New Mexico. And I think that’s the first thing that really draws people into our state. Right? The land of enchantment, the land of entrapment, um, has those connotations. Um, but it is the beauty, um, and so within that, falling in love with nature, falling in love with the isolation, the ruralness of our, our communities, um, I think there’s also this unintended consequence that people tend to not realize the occupancy that was here. Right. That’s been here for hundreds and thousands of years.

Wade Roush: Jason Garcia was also a panelist that night. He told the story about how O’Keeffe saw Pedernal as her private mountain. And toward the end of the evening, he responded to one audience member’s question about what tangible steps the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum could take to build bridges back to the communities who feel left out of the conversation. Listen close, to his answer, because this is where the idea for the exhibit starts to be born.

Jason Garcia: And I’m aware that O’Keeffe Museum opened in 1997, which has been 23 years. And in those 23 years, you know, I’ve never been in the actual exhibition space. I’ve been into the gift store and that’s it. So, you know, I think that’s part of it, of being, you know, there are some exclusivity to the museum. Um, I’m not too sure. I in my research, you know, I looked at how much tours were $45 a person to take a tour of the museum, that’s a little bit out of my price range, you know?.… So I think that’s something that should be, um, something to thought about or even, you know, do like the, uh, Indian Pueblo Cultural Center or the um, or Institute of American Indian Arts Museum, where, you know, you offer a free admission to Tewa people. You know, maybe you have to show your tribal ID card, you know, but that’s something that might be an option as well.

Corinne Sanchez: Like, I feel like in this country, we get stuck on the past of where we’re we’re honoring these personalities. Right. Um, you know that for any of us, we’re we’re all contributors to our wellbeing in our communities. And so we highlight certain leaders or we highlight certain people, um, when it’s really all of us that are really contributing to the realities of our community. So, again, how are we rethinking and having these conversations?

Wade Roush: I think it’s fair to say that 2020 panel was one of those moments that gets people fired up around an idea. The idea, in this case, being that the O’Keeffe Museum could be doing more to welcome, and honor, and highlight the indigenous people of this land O’Keeffe herself had loved so much.

<sonic interlude>

That idea didn’t burn out – it stuck around. And after the pandemic, Jason Garcia learned about a grant opportunity with the potential to fund a partnership between a native artist and a local nonprofit.

I had a chance to sit down with Jason and Bess Murphy and I asked them to tell the whole story from the beginning.

Jason Garcia: Yeah, yeah, in the beginning. It was a dark and stormy night. Call me Ishmael. Uh, so I think, uh, the original idea or some of the original seeds that were planted for Tewa Nangeh come out of the, um, 2020 “This is not O’Keeffe Country,” panel presentation and kind of talking about some ideas, uh, as the museum, uh, moves forward, moves into the future. And, uh, about two plus years ago, uh, I had looked into a grant opportunity that had a native artist that would partner with a nonprofit institution and knew Bess from some previous work. Had heard that she had moved over to the O’Keeffe as the Luce Fellow Curator. I know you have a long title. Uh, and so knowing that you were here and then saying like, hey, I have this idea. And so we did all the paperwork, applied for it, did not get the grant, but had already created that ball. That seed was already growing. So then we kind of took it from there. And the museum said, yes, let’s do it.

Jason Garcia: And and then also that energy, like you said, is kind of that ripple effect…How does this idea carry forward into doing a collaborative exhibition and not and you know, of like originally your first idea being like, oh, there’s a grant. So it’s like, okay, it’s Jason Garcia at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. But then like, okay, I can’t fully carry this full project on my back, or it can’t just be a solo artist. It has to be multi generational intergenerational voices and then Tewa voices, and then all the six Tewa pueblos wanting a minimum of four from each pueblo.... And then some of the ideas also grew out of, you know, our two year planning session as well too.

Bess Murphy: Jason brought this group together, and I think it was the trust that everyone had in Jason that allowed for those first conversations to be had, because there wasn’t necessarily trust with the institution. Um, in fact, there was a lot of distrust and some discomfort, I think really, when folks first came to the table to sit with us and hear about this initial idea, and there was a lot of questioning as to whether or not the O’Keeffe was really ready for this. Was there going to be, you know, censorship, or was the museum going to get upset if there was critique of this mythology? And so I think I don’t think we could have done this project any faster. I think all of that had to happen, um, because we needed to have time where we could get to know each other, where we could sit together and eat food and tell jokes and then do the hard work and do the, you know, bureaucratic work and make all of those steps meaningful. And that is slower work.

<cue Turning Corners theme music>

Wade Roush: Let’s pause for a minute for a mid-show announcement.

For more than eight years now, I’ve been part of a collective of independent audio makers called Hub & Spoke. And in every episode of this show I’m going to take a minute at the end to tell you a little something about what’s going on with other shows and producers in the collective.

Today I want to talk about my friend Erica Heilman, who makes a Hub & Spoke show called Rumble Strip.

Erica’s genius is finding unique and interesting people in her corner of Vermont and drawing them into intimate, honest conversations that inevitably, in every episode, teach you something new about our tenacity and daring as humans.

Erica’s show has been a huge inspiration for me in my own work, and now she’s involved in an important collaboration with Jay Allison at the Transom Story Lab in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. It’s called The Listeners. And It’s an effort to get more audio producers to make stories that grapple with the massive challenges facing Americans today by, in a sense, going small and local.

Erica and Jay are gently pushing people in the radio and podcasting world to make more stories that are true, that are grounded in a specific place or community, that challenge our assumptions, and that listen generously and honor ordinary lives.

To quote from the project’s manifesto, “In a time when resources for local and public-interest storytelling are disappearing, this is a small act of resistance and of hope. It’s about listening across differences. It’s a project in democracy.”

Honestly that’s also the project I’m engaged in here at Turning Corners. So I wanted to give a shout-out and thank you to Erica and Jay for organizing the project and keeping the early values of true public radio alive. You can learn more about The Listeners project at transom.org, and you can hear Erica’s show at rumblesripvermont.com.

Okay, now back to my conversation with Jason Garcia and Bess Murphy.

<cue theme music>

Wade Roush: Could I get you both to say one more time how you would define this exhibit? Because it’s like, it’s also in conversation with Georgia O’Keeffe, and some of her work is hanging right alongside the work by the indigenous artists. So, like, how do you how do you how did you come up with the right balance there?

Jason Garcia: Yeah that’s interesting to think about, what’s the right balance of work. Then thinking within the theme of, again, the “my private mountain” quote. And that was kind of the starting theme. But then also, how do we move beyond it and how do we. How do we see our work? How do we see our work? I don’t know if you would say fitting in that theme or how does it relate to the theme,? And when I say our work, I mean talk to people in general, contemporary past, ancestral and the landscape

Bess Murphy: Not to be too like Santa Fe woo woo about it, but I think it was it happened because it was the time for it to happen, and it happened the way like it all came together because it was time. Um, the O’Keeffe was ready for it. But I think also the collaborating artists were so open, it was so beautiful to realize how much of themselves they were really willing to put out into this project. The. It was this space of vulnerability, like really deep vulnerability on every side. And I think that, you know, I think as like the co-curators, I think Jason and I worked really hard to make sure that people felt cared for, you know, and I think that was you can feel that, I hope, I hope you can feel that.

Jason Garcia: And then also, I think it’s something that the community as well, too, of just seeing the, um, uh, the opening event on November 6th, 7th of how much people came out and, um, you know, the visitor numbers were out of the roof kind of thing. You know, we had the standing room, uh, waiting line to get in. And, you know, we had over a thousand plus visitors and, um, you know, having music, dance, food and just the kind of like a block community block party is essentially what it was, and having a lot of family, friends, colleagues, everybody come out for, for the exhibition was really was really amazing. So I’m really happy with the way everything turned out and, and is turning out. And the response that we are getting from visitors post opening.

<sonic interlude>

Wade Roush: I’m one of the visitors who loves the exhibit, in fact I’ve been to it a couple of times now. And now I really want to talk more about the art itself. It amounts to what the artists themselves describe in the show’s introductory panel as “an act of community storytelling.” And most of these stories are about the same land O’Keeffe painted, just from very different perspectives.

One of the storytellers is Michael Namingha. He’s a photographer and silkscreen artist who hails from the pueblo of Okay Owingeh and also from the Hopi tribe in Arizona.

His main contribution to the exhibit is a giant orange and yellow silkscreened photograph showing what looks for all the world like a nuclear explosion billowing over a mountainside.

Michael Namingha: So this is my interpretation, um, of a photograph that I took in 2023 of the Hermits Peak Fire, which was the largest forest fire on record for the state of New Mexico. And I became very attuned to a particular type of cloud formation during the duration of that forest fire, which lasted for five months. Um, and the type of cloud I’m talking about is a pyrocumulonimbus cloud. It is a cloud that is created by the intense heat of a forest fire, a volcanic eruption, or a nuclear explosion. So given New Mexico’s history with the creation of the atomic bomb. It just resonated with me. And so what we’re looking at is a photo silkscreen, um, that I created this past year. It measures 90 by 56 or 58in. Um, it’s colorations are intense orange and yellow and mixed in with a little bit of red. Um, the colorations in this piece talk about the air quality index, color chart. And so during the duration of this fire, I think most of us residents of, um, Santa Fe lived by the air quality index color chart, uh, determining our safety to engage with the outdoors. And so what happened was I’m a runner, and so I like to run almost on a daily basis. And so every day I would check to see where on the chart our colors were leading us, and the yellow, orange and red tend to be at the high end of the spectrum, which means the most particulates in the air, and so thereby not being safe to engage with the outdoors. And so a lot of my work from this series, which is titled my Disaster series, relate to that.

Michael Namingha: And so, um, in some ways, those are very beautiful colors to incorporate into the landscape, but also it’s a way of me making some scientific data visible through my art practice. Um, I’m primarily a photographer, and so a lot of my work is kind of photo documentary work of climate change, um, oil and natural gas extraction. I was, like I said, born and raised in Santa Fe, but I went to school in New York City at Parsons School of Design and moved there in 1999 and lived there until about 2007. And so during that time that I was away from New Mexico, I became to understand how quickly the environment in which I grew up in was changing. And so when I returned to the state, I realized just how quickly a lot of these ancestral homelands were being undermined by different oil and natural gas extraction, man’s intervention into this landscape. And so I wanted to create a way of documenting that.

Wade Roush: I mean, it looks to anyone who wasn’t here during the Hermit’s Peak Fire. If they all they knew was that this was a picture of somewhere in New Mexico, they might think it was a picture of the Trinity explosion at Alamogordo. Right. I mean, it looks like a nuclear explosion.

Michael Namingha: Right. And so my studio practice is actually based in New York City, um, in Gowanus. So I work with a print studio called Powerhouse Arts, where we can create these large scale silkscreens. And so, you know, members of the studio team were not sure exactly where this photo was taken or actually what it depicted. Um, and I think so when you’re not from this, this area, it is a little bit it takes a little bit of digging to, to figure out what it is you’re exactly looking at. And also the color variations add to that effect.

Wade Roush [voiceover]: For context here, you need to know that just few feet away from the silkscreen there’s an O’Keeffe painting called Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow, 1945. It shows a yellow sky viewed through the hole in a pelvis bone painted in shades of orange and siena. In other words, the same range of colors Michael used in his piece.

Wade Roush: We’re in a room full of paintings that some of which were conceived specifically in response to O’Keeffe and some of which sort of stand on their own completely. And I just wonder how you see yourself fitting into the larger argument here.

Michael Namingha: So this work, um, is specifically responding to a painting by O’Keeffe, which is this pelvis series that was painted in 1945. And I chose that painting specifically because of the date, um, 1945 and the creation of the atomic bomb. But what I also did a lot of my work is also very, uh, research based. Um, I like diving deeper into just kind of, um, stories behind, landscape stories behind other artistic practices. And so when I was looking at O’Keeffe’s Pelvis Bone series, I came across a quote, um, where she said that, um, I can read it to you. “When I started painting the pelvis bones, I was most interested in the holes in the bones. What I saw through them, particularly the blue, from holding them up in the sun against the sky, as one is apt to do when one seems to have more sky than earth in one’s world. They were most wonderful against the blue, the blue that will always be there as it is now, after all man’s destruction is finished.” So it was interesting that she was also looking at the destruction of this planet in 1945. Um, much that I am documenting it today, and also learned that she had a fallout shelter built at her home in Abiquiu that she ordered from the Sears Roebuck catalog. Um, wanting to paint the landscape after a nuclear detonation. Um, so in respects, that’s sort of where I’m coming from in relation to this exhibition. …she was very aware of her surroundings and she was from New York and came out west. Um, I kind of did the opposite. I went to New York. Um, but then coming back, you know, depicting this landscape. And it is a beautiful landscape that we’re lucky to be part of. Um, and, you know, there is a surreal quality to some of my work. And when you look at some of her pelvis bone series, you see that too. There’s a surrealism in influencing her, her compositions.

<sonic interlude>

Wade Roush: That surrealism shows up in a few more of the Tewa Country pieces, like a large bronze sculpture called Sandhills by Arlo Namingha, also of Ohkay Owingeh pueblo.

But many of the pieces are more literal expressions of the culture and land of northern New Mexico.

Maria Swazo Hinds from Tesuque Pueblo made a beautiful teapot out of red micaceous clay. She called the piece “Let’s Have Tea,” and says she was inspired by O’Keeffe’s own fondness for tea and wondering what the two of them would have talked about if they’d had a chance to sit down to tea together.

Elizabeth Naranjo Morse from Santa Clara Pueblo painted a large site-specific landscape that turns into an earthen path leading across the gallery. She also contributed a luminous painting called A Story of Stardust that shows tall cottonwood trees along the Rio Grande that have turned a rich golden-yellow.

The piece beautifully evokes the real feeling of autumn in New Mexico, but with a magical twist. Instead of a regular daytime sky there’s a starscape in the background. And the swirling reflections of those stars are visible on the back of a tiny stinkbug crawling below the cottonwoods.

Also for this exhibit, Jason Garcia went beyond his tile art to create a growing series of drawings and paintings of Tsi Pin or Pedernal.

Jason Garcia: I have 19 images of Tsi-Pin. And I’ll be adding, you know, another, uh, at least 11 to get 30 plus images. And then in that sense, you know, reclaiming, uh, the mountain for not my, you know, not only myself in terms of an artist, but then also, uh, just a reclamation, also reclaiming the mountain assertion of the mountain for Tewa people as well. And, um, it’s been a really, uh, interesting project of just kind of working on it, of looking at, uh, Visiting the mountain. I also did a residency at Ghost Ranch about a year and a half ago. And so, you know, seeing the mountain, uh, through different phases at dawn, uh, midday, evening, dusk, uh, sunset. And then, you know, nighttime as well, too, and different, um, variations of the mountain. And I and I’ve been taking pictures of the mountain prior to that, you know, and then, you know, would post on social media, say it’s my it’s my private mountain in quotations, you know, making kind of, you know, that dig at O’Keeffe’s, um, statement as well too.

Bess Murphy: Not to put words into her mouth, I think that she felt like this was a place where she could really, truly be herself. And she felt deeply, deeply, personally connected to the landscape here. I don’t think that she felt the same way necessarily about the cultures here. … Unlike many of the other artists from her time, like she wasn’t surrounded by indigenous art. She wasn’t actively collecting pottery. She did have textiles. So we know that she had, like, Diné textiles for sure that she lived with. So there were things definitely, um, she brought some of those textiles back to New York. So it it hit her for sure. And I think in her work we do see that like she was obsessed with this landscape. She painted one mountain over and over and over and over again. Um, and I think. It’s hard. Like, I constantly feel like I’m in this place where I’m like, I don’t actually feel like I want to be sort of apologizing for O’Keeffe. But I think the more time that I spend, like with her, like learning about her career, I do feel like, I mean, there’s something there that she there was love for that place. And then it got so complicated because she felt she had the sense of entitlement around it.

Wade Roush: Yeah. I mean, that was just part of her personality in a way.

Bess Murphy: She had a lot of entitlement! In many… Yes. So much of this is also how she was managing her identity, but also how the media created this identity and fed off of how what she was providing for them, then amplified it even more. And I think it is interesting to think about what it means to be a successful, like, 20th century female artist, and how she would have had to have been very actively involved in how her identity was being constructed. And, um, it worked very, very well for her to lean into this idea of like the the woman alone in the desert.

Jason Garcia: There’s a very disconnect from the community, from the landscape of saying like, this place is is desolate. There’s the animal life forms, there’s clouds, there’s, you know, ancestral spirits that are here. So you’re not alone. As a Tewa person, that’s how I see it. You’re not alone, you know. And then you do have your community, whether it’s your local indigenous community that you’re a part of or your family or, you know, as a person that lives here, you have artist community, you have work community, um, you know, that you have like maybe your bowling team community, you know, there’s so many different things …But it is part of that where, you know, she is creating this image and she is creating this brand in a sense, you know.

Wade Roush: If you were if you were doing a show about Ansel Adams or D.H. Lawrence or Marsden Hartley, a lot of what you’re saying would resonate, right? And to some extent, you can you can say, “Oh, these people were all just a product of their time.” But I’m curious, like, um, you know, what do you lose if you just stop there with that question? And and what would you lose if you didn’t ask that question?

Bess Murphy: Yeah, I think about that a lot. I mean, she absolutely was working in a period of, you know, American art history that was full of this, um, profound engagement with the southwest, with northern New Mexico very, very specifically, you know, like our place is so central to that larger history of American modernism. We can’t take New Mexico out of that story at all. And different artists approached it in different ways. Some people were deeply, deeply engaged with local communities and depicted them. And some of that is highly problematic. That’s where, like, there’s the levels of appropriation, there’s the level of sort of being really paternalistic in their approaches to indigenous communities and indigenous cultural practice, um, and extractive. And so I think, yes, we need to see them in their historic moment and we need to have that framework. But also history isn’t static. And so if we only ever read it as if it is okay because it was okay in the, you know, like 1920s, 1940s, then we’re not going to continue to evolve that history, right? We’re not going to be able to learn for it, from it and with it.

Wade Roush: And yet it seems to me like this exhibit isn’t really working to, it’s not trying to pass judgment. It’s not trying to render a verdict on O’Keeffe and whether she was right or wrong. It seems like what you’re trying to do is just kind of re-situate her within a much richer narrative.

Jason Garcia: Yeah, it is that we’re not passing judgment or condemning her or, you know, sometimes that’s too easy, if you’re just like “F O’Keeffe” kind of thing, or if you had it painted in red paint on the exterior of the of the museum, it’s like, uh, boring, you know? Okay. Yeah. Shocking. Yawn. You know, next. You know, and but, you know, the exhibition does draw up a lot of different themes of place, identity, language, uh, love of land, culture. And then does question does O’Keeffe have did she have these things in her work as well?

Bess Murphy: I think there’s absolutely space for critique of O’Keeffe in the exhibition, and that appears at various moments. But I also feel like it’s so much deeper than that. I think Jason’s right. It could have been very simplistic to gather a group of artists to just lay out everything that they saw as problematic with her. Um, but also, I think that wasn’t what the collaborators were interested in this group, and part of that is, I think. Not an implicit critique of O’Keefe as an individual, but maybe an implicit critique of the idea of having one iconic figure speak for an entire place that for this group of artists and culture bearers and creators and thinkers, O’Keefe shouldn’t be the only one telling the story of this place.

<sonic interlude>

Wade Roush: Jason, do you see the show as like an ending? I know you’ve been working on it for like 2 or 3 years. Is it a culmination for you, or what do you hope to see happen next?

Jason Garcia: I don’t see it as a culmination. I just see it more of like the germination of of ideas. The creation of ideas were just growing from this, of, you know, this is just one step and it’s kind of has it’s it’s creating that imprint. It’s it’s creating that footprint. And this is inspiring future Tewa generations as well too. Um, so that’s I that’s how I see it as, as just it’s a huge ripple. Ripple effect.

Wade Roush: Ripple effects. I love watching that kind of change.

It’s an extraordinary thing for a museum dedicated to a single artist to take the time to reconsider aspects of her legacy, and to ask what wound up getting hidden behind the long shadow that legacy cast.

Nobody involved in this story is trying to tear down Georgia O’Keeffe.

But there’s an understandable level of tension and distrust between the native artists of the West and Southwest and the people and institutions that represent the established Anglo-American art world.

O’Keeffe herself may have been a fierce individualist, but she was also undeniably part of that establishment.

And this tension could have persisted forever.

But in at least this one case something different happened, thanks to a shared vision that emerged across years of careful, patient collaboration between Jason Garcia and Bess Murphy and all the artists who contributed to the Tewa Country exhibit or served the planning committee.

I think that’s a beautiful thing. It’s just as beautiful as the exhibit itself. And I think it will have ripple effects that change the way people see this part of New Mexico.

The same way the brilliant sun and the shifting shadows make Tsi-Pin look like a different mountain at every hour of the day and to every pair of eyes.

<cue theme music>

Tewa Country is on exhibit at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, through September 7, 2026. And for the duration of the show, admission to the museum is free for members of indigenous tribes, communities, and nations.

Turning Corners is reported, written, produced, and hosted by me, Wade Roush.

I’d like to take a minute to thank everyone who bought into the idea of the show and helped me get this first episode out the door.

That especially includes artists Jason Garcia and Michael Namingha.

At the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, I got amazing support from Colleen Kelly, Renee Lucero, Bess Murphy, and Cody Hartley.

For their help recording the bowls, bells, and chimes I’d like to thank GinaMaria Opalescent, Catherine Smith, and Ellen Petry Leanse.

Ellen deserves a few extra thank-yous as well for introducing me to Santa Fe, taking me on my first visit to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, and introducing me to the staff there.

Now, just a few words about the show itself.

This is going to be a once-in-a-while, catch-as-catch-can kind of podcast, meaning I’ll put out new episodes as often as I can in between my other gigs. If you hit follow or subscribe in your favorite podcast app, you’ll never miss a new episode. And if you go to turningcorners.org you can sign up for our newsletter, and read full episode transcripts.

I’m always in search of new stories about people making a difference in their communities, bridging old divides, and finding innovative ways to bring people together anywhere in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah or Arizona. If you know somebody like that, and you think their story needs to be told, please write to me at wade@turningcorners.org.

Our theme music is by Joel Roston of Titlecard Music and Sound in Boston, with Amelia Hollander Ames on violin and viola and Eden Rayz on cello.

The clips of Georgia O’Keeffe’s voice are from the documentary Portrait of an Artist by Perry Miller Adato.

I got valuable edits and notes on this episode from Tamar Avishai and Mark Pelofsky. Thanks you so much!

And I just want to say, because I think we’re in an era when this needs to be said: no AI was used in the making of this podcast.

Thanks for listening, and I’ll be back with a new episode … as soon as I can.

Turning Corners is a new podcast offering inspiring stories about the people and organizations working to make life better in the Four Corners states of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado. It’s reported, written, produced, and hosted by Wade Roush. The theme music is by Joel Roston of Titlecard Music and Sound, with Amelia Hollander Ames on violin and viola and Eden Rayz on cello. You can learn more about the show at turningcorners.org. We’re a proud member of the Hub & Spoke audio collective.